Freedom for the Few

Why do the self-styled proponents of freedom embrace authoritarianism and violent domination?

This is the free weekly edition of this newsletter, the entirety of which is supported by readers like you. If you’re enjoying it, consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

Ever since the Uvalde shooting, as the country has again been shown just what our lax guns laws do, as a community questions whether it can ever right itself after being so unimaginably struck down, and as a nation again appears again poised to allow the sacrifice of its children for a demented, violent ideology, one question keeps running through my mind: What kind of freedom is this?

And one answer keeps coming up: It’s a particular kind of American freedom, one deep in our country’s bones. It’s the freedom of a few men to claim radical independence as they rely on the labor of an invisible many, and cause the suffering of a wiped-away more.

Freedom is the value that gun extremists invoke when they refuse any attempt to curtail which types of deadly and military-style weapons are available for purchase, or who might purchase them. But how free is any member of a society awash in weapons? How free are any of us if the places we go in the normal course of a day — the places we shop, the places we worship, the places we send our children to learn — can so quickly turn into places of violence and death, and are not places where we can feel secure? This is freedom dressed up as tyranny. This is the freedom of domination and violent enforcement for a few, and of subjugation and persecution for the many.

I’m currently reading / listening to The Dawn of Everything (I’m late on it, I know), and one thing the book makes clear is that what we see on today’s American right — a penchant for authoritarianism, violence coexisting with religiosity, a patriarchal definition of individualism and freedom — has a long history, and not just in the US. Freedom, in a long-standing view held by various Christian sects and European men who believed themselves to be free, involved an acquiescence to hierarchy that puts white men just below God, places most others in their service, and requires everyone to suspend reason and judgment.

In the book, the authors David Graeber and David Wengrow quote French Jesuit Charles Lallemant, a missionary who spent some of the 1620s trying to civilize the Huron (also Wendat / Wyandot) people in what is now Canada. In the Wendat community, Lallemant observes widespread freedoms: Individuals do not reflexively submit to authority figures; women have control over their own bodies and their sexual lives. Decisions were often made after a good bit of debate and argument; children did not submit to their parents, and wives did not submit to their husbands. This, clearly, was a problem, Lallemant wrote — a kind of corruption that challenged the civilizing forces of faith, which required the suspension of reason and the imposition of artificial hierarchy:

“This, without doubt, is a disposition quite contrary to the spirit of the Faith, which requires us to submit not only our wills, but our minds, our judgments, and all the sentiments of man to a power unknown to our senses, to a Law that is not of earth, and that is entirely opposed to the laws and sentiments of corrupt nature. Add to this that the laws of the Country, which to them seem most just, attack the purity of the Christian life in a thousand ways, especially as regards their marriages…”

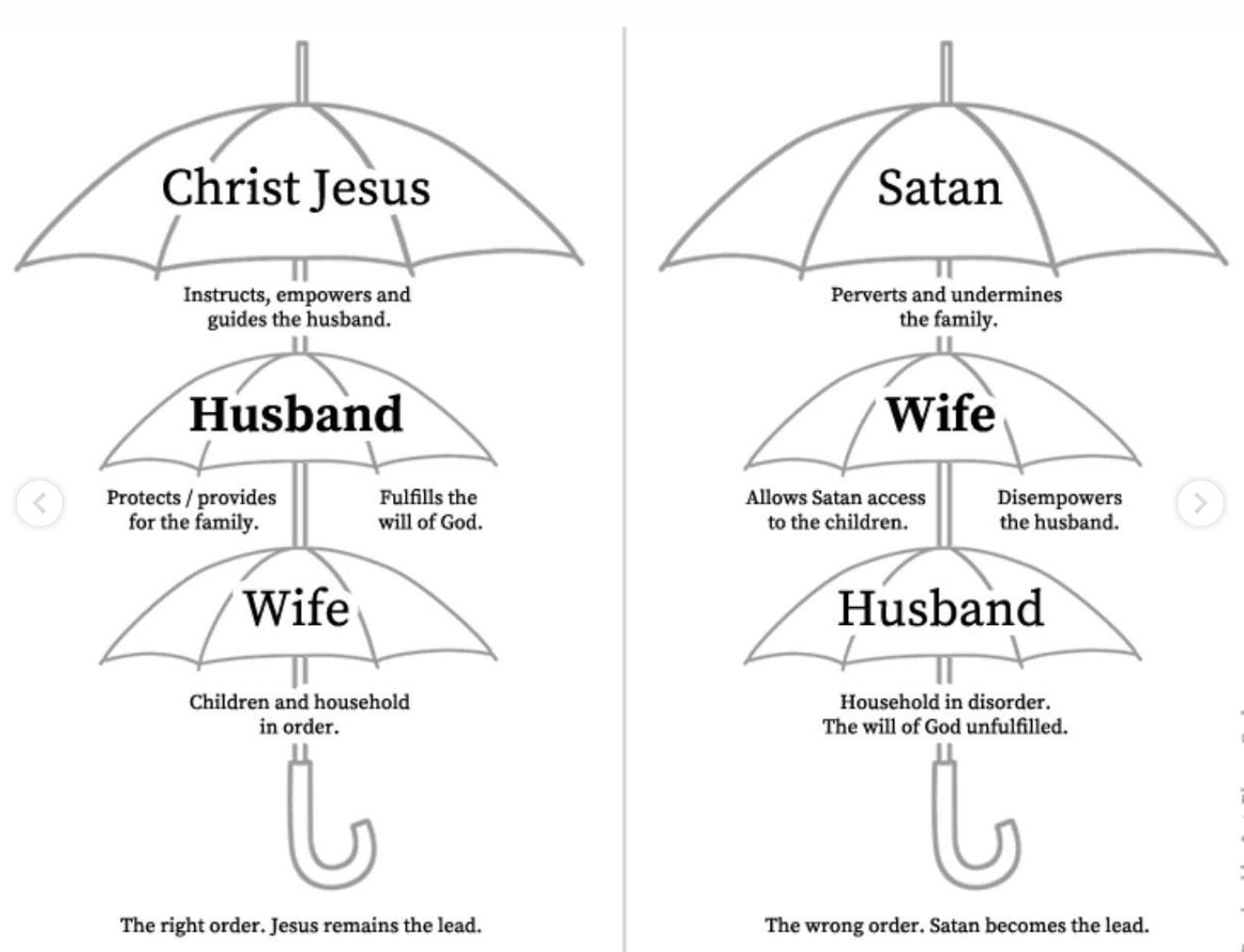

Which doesn’t mean that Christianity broadly, or Catholicism specifically, was anti-freedom, exactly. It just that freedom was more free for some than others, and that freedom always means submitting to someone — and free men get to submit to a God who whose rules they are solely empowered to interpret, while everyone else submits to them. Here’s one neat and unintentionally hilarious contemporary summation, via Humans of New York of all places:

It’s this conception of freedom that continues to animate the American right. It’s not even the Enlightenment-style freedom of individual rights; it’s a freedom that presumes freedom itself comes in limited quantities that can only be doled out to a chosen few, and that one can only be free if one also dominates other people. It’s an idea of freedom deeply intertwined with the requirements of Christianity: The demands to suspend reason and logical thought processes; the insistence on submitting oneself to one’s place in the hierarchy, and seeing any shift in the structure itself as a loss and a sin; the insistence that an authoritarian and patriarchal power structure is the only functional and civilized way to live.

Graeber and Wengrow write:

The European conception of individual freedom was, by contrast, tied ineluctably to notions of private property. Legally, this association traces back above all to the power of the male household head in ancient Rome, who could do whatever he liked with his chattels and possessions, including his children and slaves. In this view, freedom was always defined – at least potentially – as something exercised to the cost of others. What’s more, there was a strong emphasis in ancient Roman (and modern European) law on the self-sufficiency of households; hence, true freedom meant autonomy in the radical sense, not just autonomy of the will, but being in no way dependent on other human beings (except those under one’s direct control).

The important bit: True freedom meant being in no way dependent on other human beings — except those under one’s direct control. Dependence can only move up the chain. That is: A man can be dependent on God, but men are not dependent on women, any more than God could be dependent on mankind. Even a man who, by any objective measure, depends on his wife — for sustenance, for support, for taking care of him and his children — is not defined as dependent unless he has submitted his financial, social, and arguably physical power to her. And even in that case, there can be no equality, only one who is on top and one who is on bottom.

What does this all have to do with guns and our current totally untenable political moment? It helps to explain what otherwise seems like an incoherent ideology. How is it that American conservatives talk such a big game about freedom only to embrace authoritarianism? How is it that the purported right to own a gun outweighs the general public’s right to safety and even life? How can you really be free if your freedom — your personal safety, your right to keep your body in one piece — is constrained by your neighbor’s nearly unlimited freedom to pick up a deadly weapon? How can you look at the statistics on gun deaths and gun-related violence in the United States and conclude that we are a freer nation than all others?

It makes sense if your conception of freedom presumes that it simply cannot be held equally by all people at all times, and that freedom is essentially a prize for winning a contest of domination. It makes sense if freedom is a privilege reserved for the few, and if autonomy is understood as having authority not just over oneself, but over the others who naturally fall below oneself in society and the family.

How better to assert one’s dominance — to secure one’s total freedom — than to have in one’s hands an extremely efficient tool of mass death? If you want to be so free, you should arm yourself, too, and we’ll see who wins in a violent standoff.

This is right-wing freedom: A brutish battle for dominance, may the freest man win.

This also goes pretty far in explaining the conservative tolerance for, and widespread embrace of, physical violence. It is conservatives who continue to support corporal punishment, oppose stricter laws against child abuse and child marriage, and are more likely to hit their children. It was conservatives who fought against domestic violence laws and the outlawing of spousal rape. Three-quarters of political violence in the United States today comes from right-wing groups, and is often tied to white supremacy.

No wonder the people who see freedom as a limited privilege obtained by force and only available to those with the most power over others want their guns, and the obscene power over others than guns allow. No wonder people raised on blind adherence to authoritarian structure — do what God says, don’t ask questions, submit to the person above you on the ladder — are prone to authoritarian politics and often unreachable by fact and reason. No wonder the people who believe in the sanctity of a social order delivered by God on high don’t see their own dependence on others as dependence; no wonder they have no problem with authoritarianism, so long as the authoritarian they follow promises to maintain their own little fiefdom and allow them continued control over those below them.

This is the same “freedom” that handed the vote only to land-owning white men. It’s the “self-sufficiency” of Great Men who boast about going at it alone and forging their own way, never mind the mothers who do their laundry, wives who raise their children, mistresses who provide inspiration, and paid (and at many times in history, unpaid or enslaved) staff who tend to myriad needs.

This is a freedom of the self-designated deserving, deemed thus by those at the top of a clear pecking order, who have experienced themselves and enforced on others a lifetime of suspended reason. It’s a freedom that, to have it, requires others to serve and to have less. It’s a freedom delivered on the backs, and to the detriment, of all the rest of us.

It’s a false freedom borne of delusion. But that doesn’t make it any less dangerous.

xx Jill

This deep-dive piece on authoritarian values asks important questions. I think the gender component of the analysis works more than the religion component, given that recent declines in US religiosity apparently encompass conservative ranks, at least in terms of observance.

Wow. This makes sense of vexing things that otherwise make no sense. What will it take for people to prefer personhood and equality of persons to power and hierarchy?