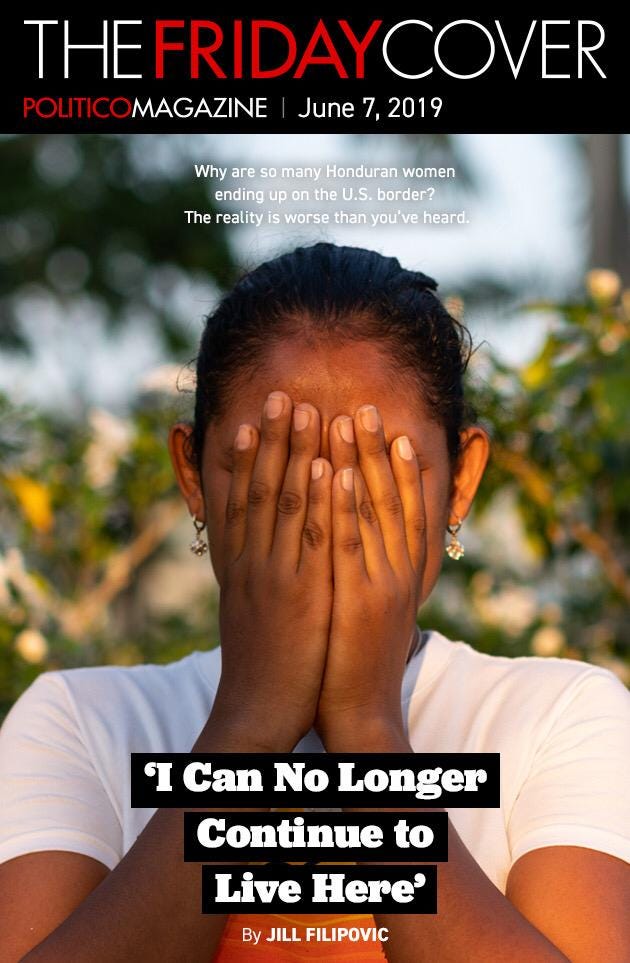

“If they’re killing you here, it’s better to go die in the desert”

Reporting on misogyny, reproductive rights and migration in Honduras.

Hello lovelies,

I hope you’ll all take a few minutes today to read this piece in POLITICO Magazine, which I reported in April and May in Honduras, along with photographer Nichole Sobecki. The story looks at the impact of Honduras’s total ban on abortion and emergency contraception. Both are wholly illegal, including for rape survivors; abortion is outlawed even when a pregnancy threatens a woman’s life, and women can face years in prison if they’re caught ending a pregnancy themselves. Honduras is also in the throes of an epidemic of violence against women, and banning the emergency pill and safe abortion means that the cost of being raped and impregnated grows exponentially higher – the trauma of having control over your body violently taken away is only magnified when, after the attack, the state does the same.

A woman and her child rest on the floor with other participants in a migrant caravan leaving Honduras. | Nichole Sobecki/VII

TEGUCIGALPA, Honduras — In a small town tucked in the hills outside Tegucigalpa, there is a stuffed gray bunny rabbit that knows a little girl’s secrets. “I tell him all my things,” she says. “About how I’m doing, and when I feel sad.” She feels sad a lot lately. “I start thinking about things that I shouldn’t be thinking,” she says.

There are a lot of things she shouldn’t be thinking. She is 12 years old and just weeks away from giving birth to a baby.

Sofia and her mom told me her story when we met at a women’s shelter in mid-April. Sofia (like others interviewed for this story, she asked me not to use her real name) was raped by a family member of her mom’s boyfriend. She still doesn’t totally understand what pregnancy means or what childbirth entails, but she knows the delivery is looming, and that scares her. “At first, she said that she did not want to have the baby,” Sofia’s mom told me. “She said that she wanted to commit suicide.” When doctors told Sofia she was pregnant and explained that pregnancy meant she was going to have a baby, Sofia, in her soft, small voice, asked whether she could have a doll instead.

When Sofia’s mom found out about the rape, she reported it to the police, and now the man who did it is in jail. But his family kept threatening them, and Sofia and her mom have good reason to worry about what happens once he’s out. Most crimes like this—more than 90 percent—aren’t even prosecuted in Honduras. The few women who do see their attackers go to jail are offered little protection when those sentences end. “If he comes out,” Sofia’s mom says, “I am afraid for my life and her life, too.”

What do you do when you fear for your life and the state won’t protect you? Or if the state might make your already tenuous situation worse? The fraught calculations that face Sofia and her mom are endemic across Honduras, a country that remains in the grip of a rash of violence against women and girls. For some, the answer is simple and disruptive: They have to leave. When exhausted families, mothers toting babies and young women traveling alone arrive at the southern border of the United States, it’s not just gang violence or criminality in general that they’re fleeing. It’s also what Sofia whispers about to her bunny: men who beat, assault, rape and sometimes kill women and girls; law enforcement that does little to curtail them; and laws that deny many women who do survive the chance to retake control and steer their own lives.

Top: “Sofia,” 12, sits on a mattress in the bedroom she shares her with family in Tegucigalpa, just weeks before she gave birth to a baby girl after being raped by a family member of her mom’s boyfriend. Bottom: “Mercedez,” 19, nurses her young daughter in a women’s shelter in Tegucigalpa. | Nichole Sobecki/VII

I hope you will read the whole thing. And if you think it’s worth sharing, I would be ever so grateful. At a time when migrants are talked about as vermin at worst or simply statistics at best, it’s crucial to understand the human beings behind the numbers, and to see the faces that (hopefully) start break down the ugly rhetoric. There are so many more stories to tell from Honduras that are necessary to paint the full picture of what’s driving migration, including the deadly and destructive role of U.S. intervention and the 2009 American-backed right-wing coup; the predatory practices of multi-national companies that destroy the environment, devastate communities, exacerbate climate change, and exact a huge toll on human life; and a struggling economy that leaves many desperate to put food on the table and survive day to day. And of course none of these threads is fully separable from the others. In this piece, I tried to illustrate one factor among a complicated many. There is much more work still here to do.

This piece is one part of a multi-country project that Nichole and I began a year ago, and it publishes the same day that we are leaving our final country (Uganda). It feels good to see some of these stories see the light of day, to get eyes on them and see how the resonate.

These are also hard stories to write and to report. Every single woman I talked to in the course of reporting this project broke off a piece of my heart. Some, like Sofia, whose story I tell in the POLITICO piece, continue to weigh heavy on my mind, and I imagine she will live there for the rest of my life. It is still impossible for me to accept the fact we live in a world where men rape little girls, and the state forces those girls to become mothers.

Interviewing Sofia was also one of the more challenging reporting experiences I’ve had. I talk to a lot of trauma survivors for my job, and that’s not new – in a past life, when I was a corporate lawyer, my primary pro bono practice was gender-related asylum claims, which meant interviewing repeatedly and in great detail women who had suffered a litany of horrors and sought refuge in the United States: A woman who survived decades of domestic violence and rape from her gang member husband; an HIV-positive trans woman who was horrifically attacked simply for existing; a lesbian woman who saw the full force of the state literally come down on her body; and young woman who was forced into FGM and early marriage with a much older man (all of these women were granted asylum, and now reside legally in the United States). In my work as a journalist, I focus on reproductive rights and sexual violence – of course I talk to a great many women who have survived rape and abuse, and a great many whose trauma is compounded by lack of access to safe and non-judgmental reproductive health care.

But I don’t talk to a lot of traumatized, pregnant children who should be finishing up elementary school, not preparing for motherhood.

When you’re out reporting, you don’t necessarily know what you’re going to find and who you’ll wind up talking to. I didn’t know I would be interviewing Sofia, or anyone of her tender age, until just before it happened. While I’ve read extensively about trauma-informed interview practices and have attended various workshops to hone those skills, I have not been officially trained in talking to anyone, let alone traumatized kids. I am not a psychologist or a therapist or even a mother. I am always feeling my way. With every woman and girl I talk to, and especially with girls as young as Sofia, I feel an immense burden to do two things: To get the story so I can make the process of talking to me actually worth it (what’s the point of asking someone to tell a hard story if it’s too thin to use?), and to not compound the trauma of what she’s already survived by asking the wrong questions, or asking necessary questions in the wrong way. For Sofia, that meant that I made the call to not ask her about the rape at all.

I imagine other journalists might have handled this differently. Could the story have been richer and more detailed if I had asked her probing questions about what happened? Yes. Did it feel worth it, to me, sitting in that room with a soft-spoken, heavily pregnant child, to pry into a topic that was so raw and painful? No.

Instead, I interviewed Sofia’s mom first, getting the necessary details from her and from medical and legal documents she let me see. And that was enough.

One thing I fundamentally strive to do when I’m reporting is to make the stories about more than just the worst thing that ever happened to someone. Every human being on earth is more than just their single most awful moment. And so I spend the overwhelming majority of these often hours-long conversations on other things: Where she grew up and what her family is like; what she likes to do and what brings her purpose and joy; what she imagines for her future, and what she hopes for herself and her loved ones. I hope when I write about all of these women, I’m able to sketch in some of the details of a whole life.

With Sofia, that meant we talked about school, her friends, her favorite stories, and her hobbies. She likes to read, and she really likes to draw – her bedroom walls are taped full of illustrations of flowers. She also likes cats and has a skinny yellow dog who she loves. We did talk about her fears of childbirth, and how much (or really, how little) she understands about what’s happening to her body, but kept it minimal and sandwiched between lighter dialogue. She told me about her favorite thing: her stuffed bunny rabbit, her conejito, who she talks to when she’s sad. “I tell him all my secrets,” she said, and in that moment, I felt like my heart might fall right out of my body.

After our chat, we went to her house so Nicki could photograph her, which in the best cases can be a little fun (and certainly felt that way with Sofia, who seemed to find us at least somewhat amusing). Nicki and I both give this kind of work a lot of thought, and always try to bring a little levity to the final moments of these interactions.

Here in Uganda, I also talked to several girls who have survived unimaginable hardship, including rape – girls who are just girls, who are little, who were attacked at school or on their way home from it. I will tell their stories in more detail as this project progresses. But one, who also became pregnant, talked to me for a while about what she called “the problem.” As we spoke, I asked her about animals at home, and she said she had a sweet goat. I said I have two funny kitties, and showed her photos of Pete and Anchovy. She likes to draw, and in my reporting notebook, she left me a little illustration of a curly-tailed big-eared cat.

This girl, too, I know I will carry with me.

Top left: Heydi Garcia Giron and her two children outside their Tegucigalpa home. The 34-year-old mother survived a machete attack from her daughter’s father, which nearly severed both her jugular and the nerves in one of her ams. She’s seeking asylum in the U.S., but the process is slow and daunting. Top right: An old photo of Garcia Giron with her son, Daniel, is on display in their home. Bottom: On a discarded bureau in a closet, Garcia Giron’s husband hand-painted a message to his two children: ”Daniel y Andrea, te amo. Papi.” | Nichole Sobecki/VII

It seems worth mentioning here that the journalism sausage is made with a lot of hands — many more than just the person whose name appears in the story’s byline. For this piece from Honduras, we worked with the most phenomenal translator, Jenny Nuñez. When you’re interviewing trauma victims in a language you either don’t speak or only kinda-sorta speak (that’s Spanish for me), it’s crucial to have someone who can use your exact, carefully-chosen words and phrasing, and who can take the same careful tone. That was Jenny: She was such a deeply empathetic but still professional presence in the room that I can say without a doubt that we simply would not have gotten these stories without her.

The women (and a few men) Nicki and I have worked with on this project have been an incredible blessing, so unusually across-the-board fantastic that we’ve said, many times over, that it’s almost like the project is a lucky charm. From Colombia to Bangladesh to Honduras to Uganda, there has not been a weak link among the many fixers and translators we have relied on – and in every place, it has been the local women we’ve relied on who have made the project possible. As more pieces of this come out, I will write about each of them individually, but in Honduras there are several other women worth mentioning in addition to Jenny. Jennifer Avila, a talented local journalist, was a great help in securing many of my initial interviews with local advocates. Maria “Ale” Rincon did a translation pinch-hit for us, and gamely worked a 12-hour day which included hopping into a police truck and driving through some pretty tough neighborhoods (very much not what she signed up for). And Óscar Curros and his team translated and transcribed thousands of words to make the actual writing of this piece possible.

The financial support for this story came from IWMF, which generously gave us a grant to fund the on-the-ground reporting (journalism: it doesn’t pay for itself!). My fellowship at New America was also instrumental in giving me the time and space to report this project and, importantly, to write the final story. And of course POLITICO Magazine, and my wonderful editor Margy Slattery, polished and published the thing, and brought it into the universe.

These stories take a village.

(They also take serious money. If you can afford to, pay for the journalism you value!)

Posters pasted around downtown Tegucigalpa read “Yo no quiero ser violada,” or “I don’t want to be raped.” | Nichole Sobecki/VII

Thank you, as always, for reading.

xx Jill