Scenes from another life (up in the air, eastern DR Congo, February 2014)

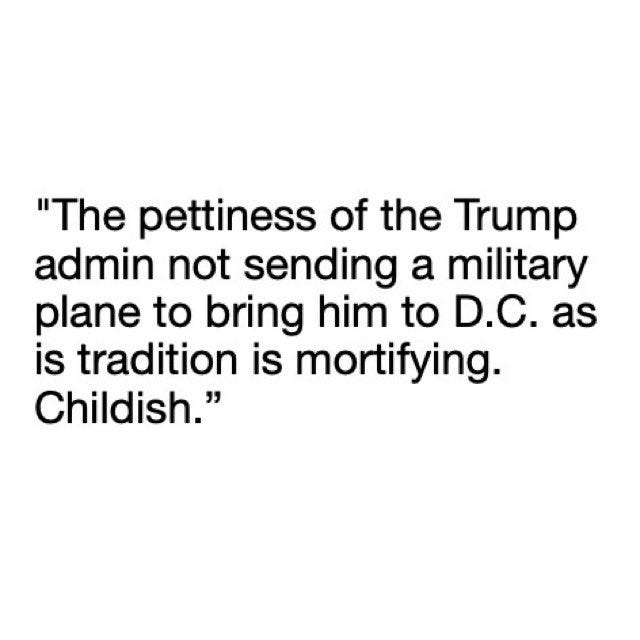

Even if you are not a Very Online person, you may have seen this story about the New York Times’s decision to fire freelance editor Lauren Wolfe, after Wolfe sent out two tweets on Inauguration Day that a right-wing outrage mob decided were biased in favor of Joe Biden. These are Lauren’s tweets, via Yashar:

According to the Times, there’s more to the story. “There’s a lot of inaccurate information circulating on Twitter,” the paper said in a statement. “For privacy reasons we don’t get into the details of personnel matters but we can say that we didn’t end someone’s employment over a single tweet. We don’t plan to comment further.”

It is totally within the realm of possibility that, as an editor who worked on a freelance contract, Wolfe’s tenure at the Times had run its course; they could have decided that she wasn’t a good fit, or maybe they decided to hire someone else in a permanent role, or perhaps there were previous social media concerns and this was the final strike. Freelance employment, I can attest, is a tenuous thing.

But none of that absolves the Times’s handling of this matter. Because, whatever happened in private and behind the scenes, what happened in public sends a clear and dangerous message: That the New York Times will bow to the outraged howls of the right wing, even when they’re crying wolf (no pun intended).

You don’t have to defend Lauren’s tweets as good to say that her firing was bad. She deleted the second tweet because it was factually incorrect (Biden chose to take a private plane to the inauguration), but that doesn’t seem to be the heart of the objection. Instead, conservatives (and a very few self-identified leftists) say Lauren’s tweets evince unconscionable institutional bias on behalf of the paper.

The Times, like most mainstream news outlets, tries to be fair-minded and balanced; that often manifests as criticism of a politician being ok, but praise being professionally inappropriate. The job of a journalist is to be adversarial to those in power: not supportive of any particular politician, and antagonistic to all of them. From that frame, you can see how these tweets would have raised some eyebrows internally at the Times. At worst, though, that makes Lauren’s tweets a misdemeanor worthy of a talking-to, not a firing offense.

It’s also worth taking a step back and asking whether the fundamental job of a journalist — being unrelentingly tough on and adversarial to those in positions of power — also requires being only a critic. Is there room for expressions of relief, humanity, and empathy within the constraints of fairness? I suspect that if a foreign correspondent, covering a place they care about but aren’t from, watched a failed insurrection, a leader who tried every possible way to steal an election, and then, finally, a democratic transition of power, that correspondent would be totally professionally in-bounds to tweet about feeling relief, or chills, or disappointment at the childish behavior of the outgoing despot. And there does seem to be a double standard here: Conservatives have so effectively worked the refs that journalists responding positively to Republicans isn’t a breach (“today is the day Trump became president;” Mitt Romney as a principled and compassionate conservative) but responding positively to Democrats can get you in hot water.

We are in a strange time, when there is a partisan division of truth. This is inconvenient for news outlets who do a kind of primitive math on journalistic fairness: If the issue is X and person A opposes and person B supports, you explain X in neutral terms, you quote from person A, and then you quote from person B, and that equals your story. But what if X isn’t and cannot be made neutral? What if X is a perversion of reality, like, “Republicans say there was widespread voter fraud” when there is zero evidence of voter fraud? In that case, the “X + A + B = Story” math is going to give you the wrong answer.

But this is how the right has rigged the calculus. They know they can break the formula if they make outrageous or simply false claims. Then, if news outlets push back and insist on the truth, conservatives claim bias. If the job of a newspaper is to tell the truth, then the scales do indeed tilt left (per Stephen Colbert, “reality has a well-known liberal bias,” at least right now in the United States). Reputable outlets, though, take concerns of bias seriously, as they should. Publications like the New York Times really do want to be everyone’s newspaper; they are the paper of record, and they don’t only want to speak to liberal America. They also know that liberals are a fairly captive audience, being less likely than conservatives to seek out media that confirms their preexisting opinions.

My sense is that the higher-ups at the Times are absolutely terrified of being seen as a “liberal” paper, and are somehow still hopeful that catering to increasingly bizarre conservative definitions of “fairness” will earn them more conservative readers, heal our national divides over basic concepts like “the truth” and “reality,” and return us to a storied time when Americans disagreed on policy and solutions, but we were mostly on the same page when it came to the basic understanding of what was happening out in the world. This is absolutely a laudable goal. But it can’t come at the expense of accuracy, and we can’t fool ourselves that “both sides” is a synonym for “fairness.”

There is a big conversation to be had about journalism and social media. Frankly, I wish it were industry standard that reporters just weren’t on Twitter; I think it’s corrosive to the profession, corrosive to originality and creativity, and corrosive to our political discourse. But here we are — the only people in media who can really afford to not be on Twitter at all are the superstars who can make a living without relying on the vagaries of the media economy. I am not one of them. I don’t think Lauren is, either. And while it would save everyone a lot of headache to just not have reporters using public Twitter accounts, publications don’t want to do that, because social media drives so much traffic to their sites. So we are stuck with reporters, editors, and writers under immense pressure to be interesting on social media (media outlets routinely ask for Twitter follower counts in job applications now), while bad actors (and this isn’t just a right-wing thing) trawl various feeds for evidence of a misstep or a bad idea. And what blows up — for good and for bad — seems entirely random, which keeps everyone in a state of perpetual insecurity: Walking right up to the edge to find the broadest reach for their thoughts and by extension their stories, without firm enough footing to know when they’ve overstepped and may fall into disaster.

I should add here that I know Lauren Wolfe. We were in eastern Congo together in 2014, when (I think!) she had the first inklings of what would eventually become this story and several others. Since then, we have stayed in loose touch. I like Lauren personally, and I have a lot of respect for her work. I know her to be a profoundly kind person, with a big heart.

But journalism is a tough industry, and people I like and whose work is good lose their jobs all the time. This isn’t about wanting to defend a woman I like. It’s that what happened to Lauren was different than a standard contract ending or even being fired — it was wrong, yes, but it is also indicative of a dangerous path media outlets seem set to walk down now that Biden is in office.

Per the Times’s statement, it could very well be that there’s a much longer backstory here. And fair enough. But even if letting Lauren go was legitimate and largely unrelated to her tweets, letting her go in the moment that an insane, frothing right-wing mob was going after both her and the Times was the worst kind of cowardice. You don’t give bullies or temper-tantruming toddlers what they demand. By publicly appearing to give in to wholly disingenuous right-wing attacks, the Times reinforced that behavior.

This isn’t the first time the right has come for a journalist, and it won’t be the last. The highest-up folks at our most respected media outlets need to demonstrate the same kind of backbone they expect from their reporters. They need to refuse to give in to the outage mobs that derive their power from institutional cowardice.

xx Jill

Are reporters not allowed to express personal opinions on their personal social media accounts? I can imagine a case of personal opinion not consistent with the values of an employer leading to termination. But this doesn’t seem to rise to that level.