The Texas Abortion Bounty Law is Anti-Choice Terrorism Codified.

How Texas let the terrorists win -- and adopted their tactics.

1The Supreme Court has finally issued its ruling on the Texas abortion bounty law: The law stands while it’s being litigated in the lower courts. I wrote about the Texas law and what it means yesterday. But there’s one aspect of the law that isn’t getting as much attention as it deserves: This is the codification of anti-abortion terrorist tactics.

The anti-abortion movement has undergone a pretty extreme makeover in the last two decades. The doctor-murders, mass clinic blockades with protesters screaming “baby killer!” at young women, demands to lock women up, and male-run anti-abortion organizations of the 1990s have given way to protesters rebranding themselves as kindly “sidewalk counselors,” groups like Feminists for Life claiming that “abortion hurts women,” the rise of anti-choice women to the most public (if not always the most powerful) roles in their organizations, and abortion opponents adopting the benevolent language of protecting women instead of the vitriolic rhetoric of punishing them. It was quite cunning, this strategy of putting a softer, more feminine face on a fundamentally misogynistic movement. What we’re seeing now, though, is what was always underneath: The same urge to publicly shame and humiliate women who don’t hew to a submissive and traditional role; the same vengeful desire to destroy the lives of anyone who helps them; and the impulse toward vigilantism and violence over due process and rule of law.

Anti-abortion terrorists aren’t a thing of the past. The pro-life movement may claim it rejects them. But it’s adopted their tactics — and in Texas, it made them law.

1984

Violence, from extreme acts of harassment to stalking to assaults to bombings to murders, have long been part of the “pro-life” movement’s strategy. The movement has specifically used the tactics of public shaming and harassment to make it extremely personally costly — and often extremely dangerous — for doctors to offer abortion care and for anyone to so much as walk into a clinic that provides abortions.

While acts of violence at abortion clinics continue unabated, most of the extreme violence, including most of the murders, happened in the 1990s, and had been building throughout the late 1970s and 1980s. The anti-abortion movement is vast and complex, but it’s also a deeply inter-connected ecosystem, with many ties between those who perpetrate violence and those who claim to speak against it — and even many of the self-styled pro-lifers in elected office. And it’s a movement that has historically zeroed in on a few geographic centers, often based on specific abortion providers who anti-abortion leaders decided to target. Among those locations: Wichita, Kansas; Pensacola, Florida; and Binghamton and Buffalo, New York.

Joe Scheidler, the founder of the group Pro-Life Action League, christened 1984 “The Year of Fear and Pain”: That year, there were 25 clinic bombings and arsons, including the firebombing of three clinics on Christmas Day in Pensacola, Florida. One of those clinics was The Ladies Center, which had also been bombed six months earlier, and became a top target of anti-abortion protesters.

The lead protester in Pensacola — the guy who is widely credited( if we can use that term) with turning the area outside The Ladies Center into a scrum of screaming men wielding gory and threatening signs, was a man named John Burt. Burt, a former Klansman, began protesting abortion clinics in Pensacola in 1983. In 1991, he bought the land next to The Ladies Center so that he could have an easier time harassing doctors and patients. He ran a home for pregnant teens and other “troubled girls” called Our Father’s House, and was also a “spiritual adviser” to Matt Goldsby and Jimmy Simmons, the two men who bombed The Ladies Center in 1984 (Burt was a suspect in those bombings, but was never charged).

In 1986, six of the Pensacola protesters, including John Burt and a religious Catholic woman named Joan Andrews, broke into The Ladies Center, assaulted women inside, and destroyed clinic property. Burt got probation, while Andrews was eventually sentenced to five years in prison, becoming a martyr of the movement in the process, receiving hundreds of letters and earning the moniker “St. Joan.” One of the people who came to town to protest her sentence was a man named Randall Terry. While there, Terry gathered his mostly-male compatriots at a Sizzler steak house (or perhaps it was a strip mall Western Sizzlin) and announced a plan to start his own ant-abortion organization, called Operation Rescue.

A year after the Year of Fear and Pain, Scheidler was invited by elected anti-abortion Republicans to testify before Congress about his group’s successes. He took the opportunity to “refuse to condemn” attacks on abortion clinics “because we refuse to cast the abortionists in the role of victim when in fact they are victimizers.”

Scheidler was an early adopter of the name-and-shame tactics that would come to characterize the height of anti-abortion terrorism, and that we see so clearly in the Texas bill. In the early 1980s, he heard about a pregnant 11-year-old rape victim whose mother, understandably, was helping to obtain an abortion. Scheidler hired a private detective to track down the little girl’s home address in a housing project on the South Side of Chicago, then posted up on a neighboring balcony and used a bullhorn to scream at her mother. When the mother refused to comply with Scheidler’s demands, he complained that she was “hysterical.” Then, he and several of his fellow anti-abortion harassers showed up at the hospital, hoping to intercept the child and her mother. When they failed, they petitioned for the girl to be removed from her mother’s care.

Using the bullhorn was a particularly inspired choice, he said: “It has a chilling effect.”

Pat Buchanan, then a White House adviser, fondly dubbed Scheidler “the Green Beret of the pro-life movement.”

Around that same time, a shadowy terrorist group called the Army of God emerged. It expressly advocated the murder of abortion providers. The group released a manual for would-be anti-abortion terrorists, detailing how to attack clinics and build bombs.

In 1986, one of Scheidler’s mentees, Randall Terry, founded Operation Rescue. The group adopted the tagline, “If you believe abortion is murder, then act like it’s murder.” The call was obvious: If you believed an actual mass murderer of children was living down the street or working in your town, would you politely wait for your elected officials to do something about? Or would you take matters into your own hands?

Or, to put it as Terry did to his followers: ”If your child or my child were in danger, we would physically intervene, with violence, if necessary, or–I should say–force.” He continued: ”If abortion is murder, then why are you people being so nice?”

Randall Terry’s extremist followers began to assault abortion clinics, blockading the doors and barring women from entering, sometimes shutting the clinics down for a period. One of Terry’s followers, a man named James Kopp, was particularly adept at making hard-to-break locks that could be affixed to clinic doors. Some 30,000 of Operation Rescue were arrested over the years, including Terry himself. The organization was explicitly patriarchal (“most people, men and women included, are more comfortable following men into a highly volatile situation. It’s just human nature. It’s history,” Terry told Rolling Stone. Earlier, he had claimed that working women were responsible for the “destruction of the traditional family unit”).

Seasons of Hate

In 1991, Operation Rescue organized a “Summer of Mercy” in Wichita, Kansas. Wichita was the target because it was home to abortion provider George Tiller, a man Operation Rescue had designated as Enemy No. 1. Over six weeks, thousands of people descended on the city, blocking clinics and the streets around them, claiming that abortion was a “holocaust.” For six weeks, protesters made it impossible for anyone to enter Tiller’s medical practice. Thousands were arrested, but Terry himself was pleased with how kindly the police behaved toward his criminal followers. Pat Robertson spoke to a stadium full of “rescuers,” encouraging them on. One “rescuer” and preacher, Phil Vollman, stood outside Tiller’s clinic and offered a sermon about “how God will cut down the evildoers,” saying, “George Tiller, your days are numbered. George Tiller, your family is in danger. God is going to deal with George Tiller and anyone else that is with him.”

George Tiller and anyone else that is with him. The Texas law, remember, doesn’t just target women — it allows anyone in the US to sue anyone who “aids or abets” a woman getting an abortion in Texas.

Encouraged by the success of the Summer of Mercy, Operation Rescue set its sights on another city: Buffalo, New York. And in Buffalo, too, anti-abortion protesters focused on individual abortion providers, this time two Jewish physicians: Shalom Press and Barnett Slepian. Christian demonstrators had for years targeted both men’s homes, harassing them and singing Christmas carols outside during Hanukkah. During the “Spring of Life” in 1992, these were the men who were targeted by name during a candlelight vigil in which Operation Rescue leader Keith Tucci, who had taken over from Terry, called Press’s medical practice a “death camp” and told his extremist followers, “This is the international day to remember the Holocaust, and this place is where the Holocaust continues to happen.” (Press’s son, Eyal, went on to be a respected journalist and has written an excellent book about this period of anti-abortion extremism; Jessica Winter’s New Yorker piece about the links between anti-abortion terrorism and the Capitol insurrection is also informative reading).

The big and thoroughly mainstream anti-abortion groups largely refused to reject these tactics. ”I wouldn’t say we’re supportive [of Operation Rescue], and I wouldn’t say that we’re negative,” National Right to Life Committee then-president John Willke told Rolling Stone. ”We’re just not a part of it.” Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority organization donated to Operation Rescue. At one point, the group was bringing in more than a million dollars in annual donations.

In the mid-1990s, Operation Rescue began to fragment. One offshoot was the American Coalition of Life Activists, which was founded in 1994 and explicitly stated that violence against abortion providers was justified. Another split came between two organizations that have changed their names a bunch of times, but that for simplicity’s sake I’ll call Operation Rescue West and Operation Save America.

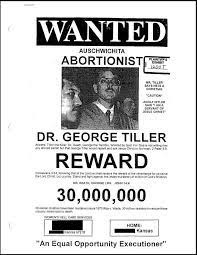

Around this time, members of the anti-abortion movement and some organized anti-abortion groups, including Operation Save America, began distributing Wild-West-Style “Wanted” posters with the faces of abortion providers on them, George Tiller among them. Pensacola’s John Burt was also an innovator of theses “WANTED” (or sometimes, “UNWANTED”) posters that would eventually characterize the vigilantism of the mid-90s anti-abortion movement. At an Operation Rescue rally for Randall Terry in Alabama in 1992, one of the Wanted posters being passed around listed the name, photo, and home phone number of Dr. David Gunn, a local abortion provider. Like today’s law in Texas, some of these “Wanted” posters offered a bounty for ending these doctors’ careers.

In 1993, Dr. David Gunn moved his practice from Alabama to Pensacola. He performed abortions at The Ladies Center, and opened a second clinic as well. The anti-abortion protests led by John Burt, then the Northwest Florida regional director of Rescue America, were still going, and Gunn became one of their top targets — where he went, they followed. On March 3, 1993, one of those protesters — and one of Burt’s close friends, a regular protester at The Ladies Center and Gunn’s other clinic, and a volunteer at Burt’s Our Father’s House for troubled teens and unwed mothers — ran into Gunn at a local gas station. That man, Michael Griffin, walked over to Gunn’s car and tapped on the window, telling him, “David Gunn, the Lord told me to tell you that you have one more chance.”

A week later, Griffin had dinner with his friend John Burt. The next day, as he joined in his usual protest outside Gunn’s clinic, Griffin stepped out of the crowd and open fire into Dr. Gunn, assassinating him. That same year, Dr. George Patterson was murdered by an abortion opponent in Alabama. Patterson’s face, too, had appeared on WANTED posters.

In 1994, two years after the Summer of Mercy targeted George Tiller in Wichita, Tiller was shot five times while sitting in his car. He survived. The woman who tried to kill him, Shelley Shannon, was an active member of the Army of God who had participated in the Summer of Mercy protests with Operation Rescue.

In January 1995, just a month after another anti-abortion activist named John Salvi went on a shooting rampage at two clinics in Brookline, Massachusetts that killed two women and wounded five other people, pro-life members of Congress joined the annual March for Life in Washington, DC. At that event, David Crane, the Southeast director of Oregon’s American Coalition of Life Activists — another Operation Rescue offshoot — released the names of a dozen abortion providers. He was, he said, “encouraging peaceful methods of exposure.”

Aiding and Abetting

Michael Griffin and Shannon Shelley became minor celebrities in the violent anti-abortion movement. “Pro-lifers” donated to their cause and to their families. Fans wrote them letters. One man named Paul Hill was so inspired by Griffin and Shelley that he dedicated himself full-time to the anti-abortion cause, becoming a regular protester with Operation Rescue members and others across the South. He went on the Phil Donahue show, where he used Donahue’s huge national platform to advocate for the murder of abortion providers. He became close with John Burt in Pensacola; Burt, a preacher, became one of Hill’s “spiritual advisers.”

After Gunn’s murder, Dr. John Bayard Britton took over the murdered doctor’s practice at The Ladies Center. Britton knew there was a risk: He got death threats, and his clinic continued to be picketed. So he wore a bulletproof vest and traveled with a security escort. On July 29, 1994, Britton pulled into The Ladies Center parking lot with his wife, June, and his escort, James Herman Barrett, a 74-year-old retired Air Force lieutenant colonel. Paul Hill walked up to their blue pickup truck and shot Britton and Barrett through their heads at point-blank range. June, sitting in the back, was sprayed with shotgun fire but survived.

An off-duty police officer should have been at the clinic, which had been bombed numerous times and seen one of its doctors killed just a year earlier, but according to then Pensacola Police Sgt. Jerry Potts, as summarized by the Washington Post, “the department's policy was not to routinely send patrol cars to the clinic on Fridays because previous demonstrations had not been violent.”

And despite Hill repeatedly breaking the law and going on national television to promote the murder of abortion providers, “There was no indication there would be any trouble from Hill,” Potts said.

Hill said that he only set out to kill Britton; Barrett was a necessary casualty but not his target. He didn’t know June would be in the car, he said, but no matter: She was an aider and abetter of abortion. “She was part of the movement,” he said. “She was there to protect him and to support and lend aid and encouragement to him. So it would certainly be justified if she had been killed.”

The Texas law allows any vigilante, anywhere in the United States, to sue anyone who “knowingly engages in conduct that aids or abets the performance or inducement of an abortion.”

In the mid-1990s, abortion opponent and American Coalition of Life Activists leader Neal Horsley launched a website called The Nuremberg Files: Visualize Abortionists on Trial. On the website, Daniel Voll wrote for Esquire, Horsley “collects the names, addresses, and photos of hundreds of doctors across America who perform abortions. Also supplied are pictures of the doctors' houses and cars, license-plate numbers, names and dates of birth of their children, churches and pastors and rabbis, social-activity information, and career profiles, as in: ‘Has been butchering babies for sixteen years.’”

Horsely, a bestiality enthusiast and unrepentant racist (he named his black cat “Negro”), had gotten his own girlfriend pregnant and then quickly abandoned her when she wouldn’t get an abortion; he never met his own child. But no matter: When, years later, his wife admitted she had terminated a pregnancy as a scared 16-year-old, Horsely blamed her for their difficulties conceiving, and made her get on her knees and beg forgiveness.

In 1998, six years after the Spring of Life targeted him by name, Dr. Barnett Slepian was shot dead in his New York home by an anti-abortion terrorist. The day after Slepian was murdered, Horsely opened up his Nuremberg Files website, typed in Slepian’s name, and struck a black line through it.

Any abortion provider who was killed had their name publicly crossed off. Those who were injured saw their names greyed out.

The man who killed Slepian, James Kopp, was also suspected of shooting, sniper-style, four other doctors in Canada and New York. Kopp was one of the fans who wrote letters to “Saint Joan” Andrews when she was in prison; he had been arrested, years earlier, for using a truck to blockade The Ladies Center in Pensacola. And he had connected with Randall Terry of Operation Rescue — Kopp was, remember, the infamous lock-maker. Prominent anti-abortion leader John Cavanaugh-O'Keefe described Kopp as “one of a relatively small group of pro-life activists who had been working to get stuff started around the country.”

He was also involved with the Army of God, and was thanked in their infamous abortion-killer manual. After killing Slepian, Kopp spent several years on the run. A network of “pro-life” activists housed, fed, and covered for him as he evaded the law.

The president of Operation Rescue West is Troy Newman, who is also on the board of the Center for Medical Progress, the anti-abortion organization that launched illegal spy operations on Planned Parenthood and released heavily edited footage. Newman moved his operation from California to Wichita in 2002 so he could be closer to George Tiller’s medical practice, making it easier to harass him. Cheryl Sullenger, who years earlier had been convicted of bombing an abortion clinic in California, was Operation Rescue West’s senior policy director and the co-author of several books with Newman. She went with him to Wichita.

In 2004, Newman, Sullenger, and their organization launched the Year of Rebuke: An effort to personally track down and publicly shame anyone who worked at George Tiller’s clinic, from nurses to receptionists to security guards. Protesters picked through the clinic’s trash to find its employee’ personal information. They stalked employees, learning their routines — where they liked to eat, where they went to church, where their kids went to school. Then they gathered outside of those places with huge placards and giant yellow arrows, pointing and shaming. They created more of the infamous WANTED posters. They did the same to anyone they believed was aiding or abetting the clinic, including suppliers or taxi drivers.

Today in Texas, it doesn’t take a vigilante to target these “aiders and abetters.” Under the law, they can now be hauled to court.

Dr. George Tiller became Operation Rescue West’s top target. And soon, they were getting lots of help. Fox News’s Bill O’Reilly mentioned Tiller on 29 separate shows, referring to him as “Tiller the Baby Killer.” He adopted the language of the Nuremberg Files and Operation Rescue, accusing Tiller of “operating a death mill.”

“And if I could get my hands on Tiller – well, you know,” O’Reilly said. “Can’t be vigilantes. Can’t do that. It’s just a figure of speech. But despicable? Oh, my God. Oh, it doesn’t get worse. Does it get worse? No.”

Eighteen years after the Summer of Mercy brought national anti-abortion attention to George Tiller, and just five years after Operation Rescue West moved back to Wichita, George Tiller was assassinated at his church. The man who killed him, Scott Roeder, had Cheryl Sullenger’s phone number on the dashboard of his car. The media covered him as a lone wolf, but Roeder was well-connected in the anti-abortion movement.

What Happened in Texas

There’s a lot more to this story, and many more cases of anti-abortion terrorism. Some of the lead terrorists and harassers have wound up in prison — John Burt, for example, was convicted of molesting one of the “troubled teens” he took into Our Fathers House (other girls have accused him of sexual assault as well). Others have faded into obscurity. Pro-choicers took on the purveyors of those WANTED posters and the threatening websites, and sometimes they won. Attacks on clinics have continued, but they no longer capture as much media attention, nor characterize the pro-life movement to the public.

The soft cover that has characterized the last decade of the anti-abortion movement was beta-tested in the 1980s and 90s, often by the same people who were also using violent tactics. James Kopp, for example, founded a so-called “crisis pregnancy center.” Randall Terry ran one as well, and would try to trick unsuspecting women into believing his center was an abortion clinic, only to show them gory anti-choice propaganda. Joseph Scheidler introduced the term “sidewalk counseling” to describe the work of accosting women outside of abortion clinics; that gentle terminology was eventually picked up by sympathetic Supreme Court justices when they did away with a law allowing abortion clinics to implement wide protester-free buffer zones.

But after the huge number of clinic attacks and all the doctor murders of the 90s and into the aughts, by the 2010s, the pro-life movement got savvier. Violence repelled the public, and so pro-lifers leaned into their softer side. Sure, they were still trying to imprison doctors, cut off access to contraception, and force women to continue pregnancies against their will, but the branding improved. They claimed their legislative efforts were about safety, not trying to regulate clinics out of business; they claimed they, not feminists, were the ones who cared about women, because “women deserve better than abortion.” The legal strategy became one of chipping away at abortion rights rather than trying to overturn Roe wholesale. Some activists did carry on where the Randall Terrys of the world left off — James O’Keefe, the Center for Medical Progress, and their gonzo, heavily-edited recordings are one example, and abortion clinics remain inundated with protesters — but the movement generally became more adept at public relations.

And then Donald Trump was elected president, and installed three staunchly anti-abortion judges to the Supreme Court, and more than 200 to the federal bench.

Now, the anti-abortion movement is more empowered than its ever been. They know that this Supreme Court may just be willing to overturn Roe v. Wade and propel American women back to the Bad Old Days. And so it’s telling to see which laws the anti-abortion movement chooses to push, and what they try.

What they’re trying in Texas is the codified version of the anti-abortion movement’s long history of vigilantism, public campaigns of tar-and-feathering, and bounty-hunting.

The same thing that the supposed “fringe” abortion opponents of Operation Rescue did with their WANTED posters? Now every person in the US is empowered to track down any Texas abortion provider and sue them. The harassment not just of doctors, but of anyone perceived as aiding and abetting women ending pregnancies, from clinic staff to taxi drivers? They can now be sued under the Texas law. And that desire from violent abortion opponents to work outside the bounds of the criminal law system, to appoint themselves the arbiters of justice? The Texas law turns these vigilantes into paid plaintiffs.

The Texas abortion bounty law is novel insofar as it is a law. But bounties, vigilantism, and broad attempts to ostracize anyone affiliated with abortion rights? That’s as old as pro-life terrorism, which is as old as the American pro-life movement itself.

xx Jill

p.s. If you appreciate this newsletter and the work that goes into it and want to support feminist-minded journalism, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. If you can’t afford one, just let me know and I’ll hook you up.

Photo by Josh Johnson on Unsplash